5 Minute Healthtech Jargon Buster: Synthetic Biology

- Romilly Life Sciences

- Sep 30, 2024

- 9 min read

by Hannah Croft, Research and Communications Associate

Synthetic biology is reshaping our world by enabling breakthroughs in medicine, agriculture and environmental sustainability. From engineering cells that target cancer with unprecedented precision to creating microbes that produce essential drugs, the possibilities are vast and transformative. This cutting-edge field is not only pushing the boundaries of what is scientifically possible but also offering innovative solutions to some of the most critical challenges facing humanity today.

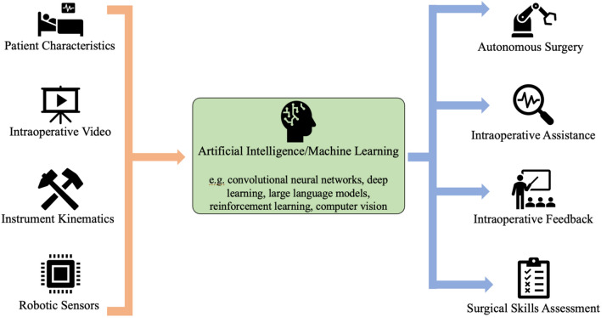

Synthetic biology (Figure 1) is an interdisciplinary field that integrates principles from biology and engineering to design, construct and reprogram biological systems and organisms, creating new functionalities and artificial genetic networks that do not occur naturally. This innovative approach treats biological components as “molecular Lego units”, enabling the development or redesign of complex biological systems [1,2,3].

Figure 1 shows an overview of Synthetic Biology [5]

Engineering biology extends these synthetic biology concepts by translating them into practical applications that address real-world problems. It spans the entire innovation process, from initial research through to the commercialisation and application of new technologies. Engineering biology contributes significantly to various sectors such as energy, environment, food, healthcare, and manufacturing, driving economic growth and promoting sustainable practices [4].

Foundations and techniques

Synthetic biology employs a diverse array of tools and techniques to design and construct novel biological systems. The following are some of the foundational methods used in the field:

DNA synthesis & DNA sequencing

DNA synthesis and sequencing are crucial tools in synthetic biology, enabling the creating and analysis of genetic material with high precision and efficiency. DNA synthesis allows researchers to construct novel DNA sequences from scratch (de novo), including genes, regulatory elements and even entire genomes. This capability is fundamental un synthetic biology, where the design and construction of new biological systems or the design of existing ones are key goals. For example, synthetic genomes can be created to study minimal life forms or to produce organisms with novel capabilities such as biosynthesis of new compounds [6].

DNA sequencing is equally important, serving as a means to verify and analyse the synthesised DNA. It ensures that the intended genetic sequences have been correctly constructed without errors, which is critical for the reliability and safety of synthetic biology applications. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies, in particular, offer high-speed, cost-effective & accurate sequencing, making them indispensable for large-scale projects in synthetic biology [6,7].

Together these technologies enable the precise manipulation and verification of genetic material, underpinning the development of innovative biological systems and the exploration of new biotechnological frontiers

Genome modification tools

The ability to precisely edit genomes is foundational to synthetic biology. Various tools have been developed for this purpose, each with distinct mechanisms and applications:

CRISPR/Cas9: The CRISPR/Cas9 system has revolutionised genome editing due to its simplicity, efficiency and precision. It uses a guide RNA to direct the Cas9 nucleases to a specific DNA sequence, where it introduces double-strand breaks. These breaks can then be repaired to introduce mutations, delete genes or insert new genetic material [8].

Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs): Engineered proteins that combine a DNA-binding zinc finger domain with a DNA-cleaving nuclease domain. They can be customised to target specific DNA sequences but require complex protein engineering [9].

Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs): Similar to ZFNs, TALENSs use customisable DNA-binding domains to guide nucleases to specific sequences. They offer greater flexibility due to their simple modular design, however, a significant limitation is their relatively large size, which can make it challenging to deliver them into host cells [10].

Meganucleases (aka Homing Endonucleases): These are rare-cutting endonucleases that recognise long DNA sequences, making them useful for targeted gene editing. However, their natural specificity is limited, which can restrict their versatility [11].

Chassis

A chassis in synthetic biology refers to the host organism or cellular platform that is engineered to carry and express synthetic genetic circuits. Common chassis organisms include scherichia coli (E. coli) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker’s yeast), and mammalian cells. These organisms are selected based on their genetic tractability, growth characteristic, and compatibility with the intended application. The choice of chassis is critical, as it determines the environment in which synthetic genes operate and impacts the efficiency and stability of the engineered system [12].

Transcriptional engineering

Transcriptional engineering involves modifying the transcriptional machinery to regulate gene expression precisely. Key components include:

Synthetic Promoters: Engineered DNA sequences that initiate transcription and control the expression levels of downstream genes. These promoters can be designed to respond to specific environmental signals or regulatory proteins [13].

Synthetic Transcription Factors: Proteins engineered to bind specific DNA sequences and regulate the transcription of target genes. These can be designed to activate or repress gene expression in response to specific stimuli, allowing fine-tuned control over cellular behaviour [13].

Applications in Health Technology

Gene therapy: Synthetic biology enables the development of gene therapies that can correct genetic disorders by introducing, removing, or altering genes within a patients cells. For example, treatments for genetic conditions such as sickle cell anaemia and cystic fibrosis are being developed using CRISPR/Cas9 [14].

Biosynthesised pharmaceuticals: Synthetic biology enables the production of valuable pharmaceuticals through engineered microorganisms, providing a sustainable and scalable alternative to traditional extraction of chemical synthesis methods. Examples include the biosynthesis of codeine and other opioids in yeast, and artemisinin, an essential antimalarial compound, in engineered bacteria or yeast. These biotechnological approaches can ensure a stable supply of important medicines and reduce production costs [14].

Synthetic vaccines: The rapid development of mRNA vaccines, such as those for COVID-19, showcases synthetic biology’s potential in creating vaccines. These vaccines utilise synthetic mRNA to instruct cells to produce viral proteins, thereby stimulating an immune response without the need for a live virus [15].

Personalised medicine: By integrating synthetic biology with patient-specific data, personalised therapies can be developed. For example, engineered bacteria have been designed to selectively target and destroy brain cancer cells. These bacteria can be programmed to home in on tumour tissues and release anti-cancer compounds, offering a highly targeted treatment approach that minimises damage to healthy cells and reduces side effects [16].

Novel materials: synthetic biology can create new materials with unique properties For example spider silk proteins have been synthesised in yeast and bacteria, resulting in strong, lightweight fibres with potential applications in biomedical devices and textiles [17].

Challenges

Despite its promise, synthetic biology faces several challenges and ethical considerations:

Biosafety and Biosecurity: Ensuring the safe use and containment use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is crucial, as there is a risk that engineered organisms might escape into the environment and interact unpredictably with natural ecosystems. Additionally, the dual-use nature of synthetic biology technologies raises biosecurity issues, as they could potentially be misused to create harmful biological agents [18,19].

Long-term Stability: Maintaining the stability of engineered biological systems over time is challenging, as factors like temperature and humidity can affect their viability and function. Robust systems that remain functional under varying conditions are crucial for practical applications [20].

Scalability and Standardisation: Scaling up from lab experiments to commercial production can be difficult due to the variability in biological systems. Standardising genetic parts and protocols is essential for consistent production and quality, though challenging due to biological complexity [21].

Minimal Equipment, Resources & Automation: To be accessible, especially in resource-limited settings, synthetic biological systems must operate with minimal specialized equipment and support. This includes developing automated and autonomous systems, such as automated DNA assembly and adaptive biological systems, to reduce reliance on skilled professionals and facilitate use in developing regions and remote areas [20].

Ethical considerations: Synthetic biology raises ethical questions, such as the moral implications of “playing God” by creating synthetic life forms and the potential socioeconomic impacts of disruptive technologies. Outdated regulatory frameworks add to the uncertainty, highlighting the need for updated ethical guidelines and policies [19].

Regulations in Synthetic Biology

As synthetic biology advances, it faces the challenge of effective regulation to ensure safety and ethical use. Many existing regulations are based on traditional genetically modified organism (GMO) standards that are outdated and no longer fully applicable. These frameworks, originally designed for slower and less complex genetic modifications, struggle to address the advances in synthetic biology, such as the ability to engineer entire genomes or create novel organisms. Current regulatory models, including the European distinction between “contained use” and “deliberate release”, often fall short when applied to new applications and products that extend beyond conventional laboratory settings. The European Union generally adopts a precautionary approach, focusing on rigorous risk assessments to ensure safety, but this can result in overly restrictive regulations that do not align with the pace of innovation. Additionally, many regulatory regimes rely on case-by-case assessments, which can limit their ability to effectively address the diverse and evolving nature of synthetic biology applications. As a result, there is a pressing need for adaptive regulatory approaches that can keep pace with technological advancements and accommodate the unique aspects of synthetic biology, ensuring both safety and the fostering of innovation in the bio-economy [21].

The Role of AI

In the future, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) will greatly enhance the design and optimisation of synthetic biology. These technologies provide advanced predictive capabilities, allowing for precise modelling and fine-tuning of biological systems. AI and ML have already improved the production of biopharmaceuticals and biofuels, and optimized enzyme and peptide engineering. As these tools advance, they will streamline the design-build-test-learn cycle, accelerating the development of new biological products and driving innovations in biomanufacturing, drug discovery, and environmental sustainability [22].

Where to find out more

Romilly Life Sciences can offer several decades experience leading the validation, regulatory approval and implementation of novel technologies including proficiency in the regulation and implementation of in-vitro diagnostics, biomarkers and therapeutic interventions based on cellular biology.

To find out how you can reach patients faster, backed by compelling evidence, contact us.

References

[1] Wang, C., Zeng, H.-S., Liu, K.-X., Lin, Y.-N., Yang, H., Xie, X.-Y., Wei, D.-X. and Ye, J.-W. (2023). Biosensor-based therapy powered by synthetic biology. Smart Materials in Medicine, [online] 4, pp.212–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smaim.2022.10.003.

[2] Del Vecchio, D., Qian, Y., Murray, R.M. and Sontag, E.D. (2018). Future systems and control research in synthetic biology. Annual Reviews in Control, [online] 45, pp.5–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcontrol.2018.04.007.

[3] Xin, F., Dong, W., Dai, Z., Jiang, Y., Yan, W., Lv, Z., Fang, Y. and Jiang, M. (2019). Biosynthetic Technology and Bioprocess Engineering. Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering, [online] pp.207–232. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-444-64085-7.00009-5.

[4] Engineering Biology. (n.d.). Available at: https://www.ukri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/UKRI-160921-EngineeringBiology.pdf.

[5] Singh, S.P., Bansal, S. and Pandey, A. (2019). Basics and Roots of Synthetic Biology. Elsevier eBooks, pp.3–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-444-64085-7.00001-0.

[6] Garner, Kathryn L. (2021). Principles of synthetic biology. Essays in Biochemistry, [online] 65(5), pp.791–811. doi:https://doi.org/10.1042/EBC20200059.

[7] emea.illumina.com. (n.d.). Synthetic Biology | Definition, applications, and NGS benefits. [online] Available at: https://emea.illumina.com/techniques/popular-applications/synthetic-biology.html#:~:text=Synthetic%20Biology%20Applications&text=NGS%20technology%20equips%20researchers%20with.

[8] Schmidt, T.J.N., Berarducci, B., Konstantinidou, S. and Raffa, V. (2023). CRISPR/Cas9 in the era of nanomedicine and synthetic biology. Drug Discovery Today, 28(1), p.103375. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2022.103375.

[9] Osborn, M.J., DeFeo, A.P., Blazar, B.R. and Tolar, J. (2011). Synthetic Zinc Finger Nuclease Design and Rapid Assembly. Human Gene Therapy, 22(9), pp.1155–1165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/hum.2011.072.

[10] Baltes, N.J. and Voytas, D.F. (2015). Enabling plant synthetic biology through genome engineering. Trends in Biotechnology, 33(2), pp.120–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2014.11.008.

[11] Hoy, M.A. (2019). Transposable-Element Vectors and Other Methods to Genetically Modify Drosophila and Other Insects. Elsevier eBooks, pp.315–344. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-815230-0.00008-x.

[12] Adams, B.L. (2016). The Next Generation of Synthetic Biology Chassis: Moving Synthetic Biology from the Laboratory to the Field. ACS Synthetic Biology, 5(12), pp.1328–1330. doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.6b00256.

[13] Engstrom, M.D. and Pfleger, B.F. (2017). Transcription control engineering and applications in synthetic biology. Synthetic and Systems Biotechnology, 2(3), pp.176–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synbio.2017.09.003.

[14] Yan, X., Liu, X., Zhao, C. and Chen, G.-Q. (2023). Applications of synthetic biology in medical and pharmaceutical fields. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, [online] 8(1), pp.1–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01440-5.

[15] Kwon, S., Kwon, M., Im, S., Lee, K. and Lee, H. (2022). mRNA vaccines: the most recent clinical applications of synthetic mRNA. Archives of Pharmacal Research. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12272-022-01381-7.

[16] Jain, K.K. (2013). Synthetic Biology and Personalized Medicine. Medical Principles and Practice, [online] 22(3), pp.209–219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000341794.

[17] Bittencourt, D.M. de C., Oliveira, P., Michalczechen-Lacerda, V.A., Rosinha, G.M.S., Jones, J.A. and Rech, E.L. (2022). Bioengineering of spider silks for the production of biomedical materials. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, [online] 10, p.958486. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2022.958486.

[18] Weale, A. (2010). Ethical arguments relevant to the use of GM crops. New Biotechnology, [online] 27(5), pp.582–587. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbt.2010.08.013.

[19] Douglas, T. and Savulescu, J. (2010). Synthetic biology and the ethics of knowledge. Journal of Medical Ethics, 36(11), pp.687–693. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2010.038232.

[20] Brooks, S.M. and Alper, H.S. (2021). Applications, challenges, and needs for employing synthetic biology beyond the lab. Nature Communications, 12(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21740-0.

[21] Sundaram, L.S., Ajioka, J.W. and Molloy, J.C. (2023). Synthetic Biology Regulation in Europe: Containment, Release, and Beyond. Synthetic Biology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/synbio/ysad009.

[22] Hector García Martín, Stanislav Mazurenko and Zhao, H. (2024). Special Issue on Artificial Intelligence for Synthetic Biology. ACS synthetic biology, 13(2), pp.408–410. doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.3c00760.

Comments